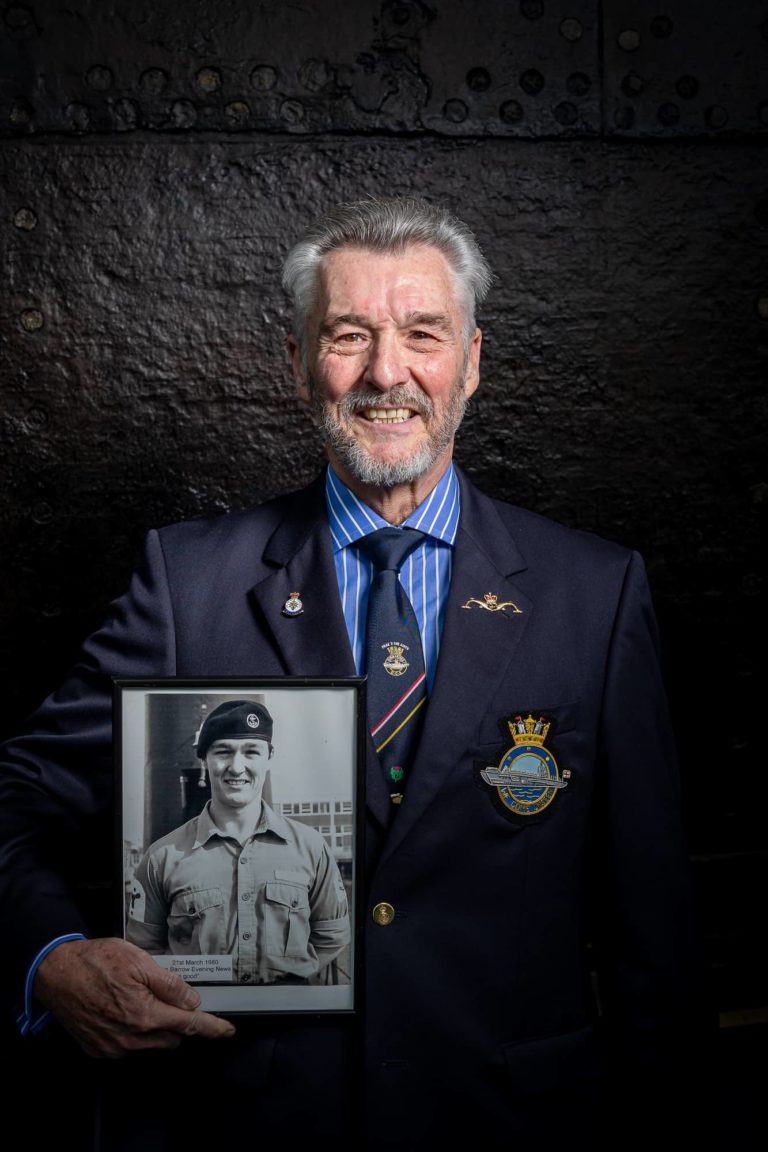

Ian Moore – Depth charged by Russians on sneaky patrol

The first one, long hot summer of 1976, when everybody was basking in their sunshine in this country, just as the sun came out here in the March, we left for a 6-month sneaky Patrol. Sneaky Patrol is something where we’re going spying basically. That’s what it essentially was, but we were going to be away …

Simon: Taking photographs or listening to things or …

Yeah, we were going to be away for 6-months and it was going to be 6-months dived, so everything was topped up to the absolute maximum. The food that came onboard was just absolutely ridiculous. We ended up with what we call a ‘false deck’ running through the submarine which is where we packed in as many tins as we could, so we literally created another deck all the way through the submarine. We quite literally ate our way through the submarine with all the food that we had onboard.

Simon: Getting more ceiling height as you …

Yeah, so because of the additional height that we put onto the decking, everybody kept on banging their head everywhere because we were so used to just dodging things around that was above us. We got to a point where that didn’t work, right, ok, fine, no problem, so yeah, we would eat our way through the submarine. But the idea of that was that we were to dive just south of the Isle of Wight in March, and the plan was that we were going to surface just south of the Isle of Wight 6 months later in the September. From diving just south of the Isle of Wight, we would go down out into the Atlantic, through the Bay of Biscay, down into … and then we’d do a dived transit of the Gibraltar Straits. We would traverse the whole of the Mediterranean, down into the Aegean, to the entrance to the Black Sea at the eastern end of the Med, because we were told that the brand-new Russian Aircraft Carrier, the Kiev, was coming out on sea trials into the Mediterranean, and we were there to meet her and greet and we were going to spy on everything that she was actually doing. And spying for our side of things was that we would see if we could get underneath her and photograph all her underwater fittings so that we knew what sort of equipment she was actually fitted with. We would listen to all the ship’s noises so that we’d learn to recognise it from a distance. We’d also watch all the routines that they were actually doing [telephone rings] … sorry about that …

Simon: So, you were saying, listening.

We would listen to all the noises that the ship actually makes and what that would enable us to is all those recordings would then be sent out to all other submarines, so that at any time in the future, if the Kiev was operating in their area, they would be able to pick it up and they would be able to analyse it and recognise that it was actually the Kiev without even ever seeing it. But as with all these things, for a new 1st of the Class, she was escorted out by a whole troop of Destroyers, Frigates, aircraft and submarines.

Simon: ‘Cos they know that you’re going to be there.

They know that we’re going to be there, they know that we’re going to try and spy on them, so it was just a matter of we went down there and we stayed dived and waited for her to come out and obviously the intelligence that we had was good enough, because she appeared when she was supposed to have appeared, and we then spent the next few weeks following her around and watching what she was doing and how she was doing things, and making recordings of … because she was there to exercise, so we were watching the Russian Exercises and we were making notes of everything that they did and how they did it. Obviously part and parcel of what they do is Anti-Submarine Exercises, and that’s when it got a little bit scary (laughs) because when they went in to the Anti-Submarine Exercise mode, we got caught, and they started chasing us all round the area, and they were dropping …

Simon: How do you know that they’re chasing you?

‘Cos they suddenly went active.

Simon: What does active mean?

As opposed to the surface ships and the submarines, we knew there was a couple of submarines there, for the most part, a submarine relies on stealth. It relies on being silent, completely silent, so therefore it just listens. It doesn’t make any noise, it just listens. When you actually pick up a positive contact on something, you call it ‘active’ which is where you’re actively making noises yourself to pick up those other submarines. It’s almost like using radar, where they will send a ping out into the water, and if it hits the hull of your submarine and bounces back, they know they’ve got a target. They know we’re there. And they suddenly went active to tell us basically, ‘we know you’re there and now’s your chance to actually leave the area’.

Simon: Right, it’s a warning sign.

Yeah, it is a warning, and we weren’t going anywhere. The Captain at the time, JBT, James Bradley Taylor, he was a little bit gung-ho and he said, “No, we’ll stay around, we’ll evade this and we’ll stay out of the way and things’ but we never did. They kept on chasing us down and every so often they were dropping depth charges over the side.

Simon: Of a ship.

Of a ship, yeah, they were dropping depth charges which is a usual thing. I mean when the Russians are spying on us, we will actually drop scare charges basically over the side a ship to let them know that we know you’re there, so therefore your cover’s been blown, go away. This lot decided … the Russians decided that they took great umbrage at the fact that we were actually there, and they were dropping what we believe was to be 50 kilo, 200-pound charges over the side that were so close to us, that we actually lost 2 sections of the casing off the submarine itself. The casing section.

Simon: Blown off?

A casing section essentially is a fibreglass section of the submarine that you look at when you’re actually looking at the external part of a submarine, so it free floods inside but it’s basically it’s made of fibreglass and it comes in sections. Each of those sections probably weighs about half a tonne, is held on by over 100 stainless steel nuts and bolts, and they hit us with enough power to actually dislodge two of those and we lost those completely. We also lost one of the Indicator Buoys, which caused absolute chaos back here, ‘cos an Indicator Buoy is used in an Escape, that when you actually are on Escape, you release the Indicator Buoy to tell the world and especially the Admiralty here, that you’re in trouble, and we lost the Indicator Buoy and we didn’t know it.

Simon: That went off and basically is saying, “Hey, we’re in trouble.”

Yes, that went up to the surface, we were deep, we didn’t know that we’d actually lost this thing. The cable had been severed ‘cos normally there’s a couple of thousand yards of cable attached to this thing, so that if you’re on the bottom, and the Buoy is on the surface, you don’t tie up to it or anything like this, but there’s a cable and you can contact the submarine below you, if you’re lucky. It depends on what depth of water you’re actually in. But that cable had been severed, so we had no idea that we’d lost the Indicator Buoy. The Indicator Buoy hit the roof, it did what it was supposed to do, it sent out a Distress Call to the Admiralty in London and all the rest of it, the whole of NATO was put on high alert for a sub sunk, which is one of your worst-case scenarios, a bit like the Kursk. When the Russian’s lost the Kursk and things, this is the same scenario for what they would do for us. The Indicator Buoy went up, it flashed off a signal saying that the submarine was in distress, and we had no idea what was going on.